Introduction

Whether you are a young or older cyclist, you can surrender your youth gracefully by training smarter, not by struggling against the effects of aging. Before we discuss why our present fitness may not be our potential fitness, and what we can do to close the gap, let's examine why our ability to ride fast is less now than it was when we were younger: -- Our heart delivers less oxygen to your muscles because your maximum heart rate and the amount of blood your heart can pump on each stroke decrease with age.

-- We've also lost muscle mass and produce less of the hormone needed for muscle repair.

-- We've lost more fast-twitch muscle fibers than slow-twitch muscle fibers, which makes fast, intense riding more difficult than slow, moderate riding.

-- We can't inhale as much oxygen nor exhale as much carbon dioxide because the elasticity of our lungs has decreased and the resistance of our airways has increased.

-- And we can't maintain intense riding as long as we once did, because the lactic acid produced by fast riding isn't dissipated as rapidly.

These are some of the physical ways in which aging changes us, and why we tend to prefer long, slow rides--a zone of comfort where it takes less effort to keep our present fitness than the effort it would take to continue up the mountain. Long, slow rides are a good way to surrender our youth gracefully. But there are psychological reasons to continue up the mountain, and one of them is not being satisfied with our present fitness. And unless we've been training seriously for at least five years, we have not reached our potential fitness. We can continue up the mountain, increasing our fitness well beyond the age where research predicts we will slow down.

Yes, a combination of distance (endurance) and intensity (speed) will produce your best overall performance. But you have two reasons for reducing the distance and frequency of your long, slow rides:

Standard Intervals

Intervals are the most effective way to improve your cardiovascular fitness. Pushing your heart rate into the high aerobic and anaerobic levels on a regular basis improves your heart, your lungs, your muscles, and your ability to mentally deal with the muscular discomfort of riding fast. Intervals are more effective when you:

Fartlek Intervals

When I was a competitive runner and swim-bike-run triathlete, I did intervals twice a week--on the track, on my bicycle and in the pool. They weren't fun, but I never thought of them as something I was struggling against. They were just a necessary aspect of my training so I could achieve my competitive goals: win my age division, or at least place in the top three, and improve my personal best times.

Intervals are still not fun, but they are still necessary, because I still have goals: Slow the aging process as much as possible so I can enjoy cycling as long as possible. Stay fit enough to ride with my younger friends. But intervals on the same day and the same route week after week can cause boredom and burnout. And I already ride three times a week with my cycling friends. So I don't do standard, scheduled intervals. I just add brief periods of more intense riding to my long and short rides with my friends.

In my racing days, we called this type of interval a fartlek, a Swedish word for speed play. Fartleks are a less-structured form of interval training. They allow me to be flexible, to listen to my body so I can add short periods of intense cycling when I'm feeling good. Fartleks are a great way to turn grinds into grins. Here are a few to consider:

Pole Sprints... sprint from one telephone pole to the next at your maximum aerobic speed--the edge of your anaerobic threshold. Then spin easily for 4 poles. Repeat 3 times.

Hill Repeats... as you get near the hill, select a lower gear than you normally would. Stay seated and spin fast two thirds up the climb, then shift up, stand up and pedal over the top. Let your momentum carry you over and down to the next hill.

Breakaways... last person in line charges past the group. When she's about 200 yards ahead, the pace line works to pull her back. Everyone rides easily for a few minutes, then another rider springs from the rear. Repeat 3 or 4 times.

Chases... two riders stop, allowing the others to continue in a pace line. Then the two work together to chase down the group. Repeat with pairs of riders.

Surges... stand and accelerate for 10-30 seconds, or until you spin out the gear, then sit down and spin 10 RPM faster. Hold this cadence for five seconds, then return to normal pace. Repeat 3 or 4 times every hour. Pickups... get out of the saddle and accelerate away from stop signs, over short hills, out of turns or around a car parked in your bike lane--check your mirror!

Nutrition

Keep your glycogen stores high so you can handle more intense riding. Most cyclists have enough glycogen stored in their liver and muscles for about two hours of moderate intensity. When glycogen runs out, the body begins to burn fat, which can lead to bonking. So make sure you ingest 40 grams of carbohydrate per hour during your rides. Most energy bars contain about 40 grams of carbohydrates.

Your glycogen is low after a ride, but your blood flow will remain high for an hour or so. That hour after a ride is a glycogen window during which your body will convert the carbohydrates you eat more rapidly than normal. So eat or drink carbohydrates as soon after a ride as possible to ensure adequate glycogen recovery.

Recovery

Let your body tell you when it's ready to ride again. Your body repairs itself at night, while you sleep. So make sure you get adequate rest. If you need an alarm clock to get up in the morning, you probably didn't get enough sleep.

Goals

Strive to mesh the physical and psychological side of cycling--your training and performance goals--with the social side of life--your family and friends.

Zone Training

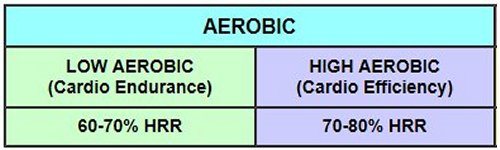

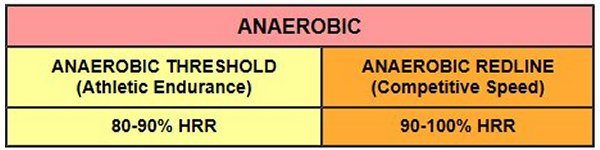

Training in specific zones is a results-oriented way to align your heart, your training and your goals. Each zone is a Training Level (TL) associated with a range of heart rates and training effects. The range of heart rates for each zone are percentages of your Heart Rate Reserve (HRR). Your heart rate reserve is the range of heart beats between your Resting Heart Rate (RHR) and your Maximum

Heart Rate (MHR). Your maximum heart rate can be approximated by subtracting your age from 220. You can get closer to your actual MHR by running on a treadmill or cycling up a hill near your anaerobic redline.

Low Aerobic... you burn fat (low octane fuel) and your heart delivers all the oxygen your muscles need. Exercise in this range of heart rates builds cardiovascular endurance. It's the Fat-Burning Zone but you'll lose more weight by burning fat and glycogen and that requires a mix of low and high aerobic exercise.

High Aerobic... you burn fat and glycogen (high-octane fuel), and your heart delivers all the oxygen your muscles need. Exercise in this range of heart rates builds cardiovascular efficiency ~ the ability to transport oxygen to and carbon dioxide from your muscles. Stroke volume, the amount of blood your heart pumps with each beat, is the key to improving fitness. You notice improvement as an ability to exercise longer before dropping back to the low aerobic zone.

Whether you are a young or older cyclist, you can surrender your youth gracefully by training smarter, not by struggling against the effects of aging. Before we discuss why our present fitness may not be our potential fitness, and what we can do to close the gap, let's examine why our ability to ride fast is less now than it was when we were younger: -- Our heart delivers less oxygen to your muscles because your maximum heart rate and the amount of blood your heart can pump on each stroke decrease with age.

-- We've also lost muscle mass and produce less of the hormone needed for muscle repair.

-- We've lost more fast-twitch muscle fibers than slow-twitch muscle fibers, which makes fast, intense riding more difficult than slow, moderate riding.

-- We can't inhale as much oxygen nor exhale as much carbon dioxide because the elasticity of our lungs has decreased and the resistance of our airways has increased.

-- And we can't maintain intense riding as long as we once did, because the lactic acid produced by fast riding isn't dissipated as rapidly.

These are some of the physical ways in which aging changes us, and why we tend to prefer long, slow rides--a zone of comfort where it takes less effort to keep our present fitness than the effort it would take to continue up the mountain. Long, slow rides are a good way to surrender our youth gracefully. But there are psychological reasons to continue up the mountain, and one of them is not being satisfied with our present fitness. And unless we've been training seriously for at least five years, we have not reached our potential fitness. We can continue up the mountain, increasing our fitness well beyond the age where research predicts we will slow down.

Yes, a combination of distance (endurance) and intensity (speed) will produce your best overall performance. But you have two reasons for reducing the distance and frequency of your long, slow rides:

- Short, fast, intense riding has more effect on fitness than long, slow distance.

- Fewer long, slow rides give you more time to recover for the next intense ride.

Standard Intervals

Intervals are the most effective way to improve your cardiovascular fitness. Pushing your heart rate into the high aerobic and anaerobic levels on a regular basis improves your heart, your lungs, your muscles, and your ability to mentally deal with the muscular discomfort of riding fast. Intervals are more effective when you:

- Limit your repetitions to 2 or 3 because most of the training effect comes from the first interval, and much less from a second and even less from a third.

- Add intervals to your training schedule only after you've got an aerobic base of at least 500 miles of riding at a steady, moderate pace.

- Pay attention to intensity (heart rate), duration (1-2 minutes), frequency (2-3 per week) and recovery (48 hours).

- Maintain the total hours you cycle per week. A combination of distance (endurance) and intensity (speed) will produce your best overall performance.

Fartlek Intervals

When I was a competitive runner and swim-bike-run triathlete, I did intervals twice a week--on the track, on my bicycle and in the pool. They weren't fun, but I never thought of them as something I was struggling against. They were just a necessary aspect of my training so I could achieve my competitive goals: win my age division, or at least place in the top three, and improve my personal best times.

Intervals are still not fun, but they are still necessary, because I still have goals: Slow the aging process as much as possible so I can enjoy cycling as long as possible. Stay fit enough to ride with my younger friends. But intervals on the same day and the same route week after week can cause boredom and burnout. And I already ride three times a week with my cycling friends. So I don't do standard, scheduled intervals. I just add brief periods of more intense riding to my long and short rides with my friends.

In my racing days, we called this type of interval a fartlek, a Swedish word for speed play. Fartleks are a less-structured form of interval training. They allow me to be flexible, to listen to my body so I can add short periods of intense cycling when I'm feeling good. Fartleks are a great way to turn grinds into grins. Here are a few to consider:

Pole Sprints... sprint from one telephone pole to the next at your maximum aerobic speed--the edge of your anaerobic threshold. Then spin easily for 4 poles. Repeat 3 times.

Hill Repeats... as you get near the hill, select a lower gear than you normally would. Stay seated and spin fast two thirds up the climb, then shift up, stand up and pedal over the top. Let your momentum carry you over and down to the next hill.

Breakaways... last person in line charges past the group. When she's about 200 yards ahead, the pace line works to pull her back. Everyone rides easily for a few minutes, then another rider springs from the rear. Repeat 3 or 4 times.

Chases... two riders stop, allowing the others to continue in a pace line. Then the two work together to chase down the group. Repeat with pairs of riders.

Surges... stand and accelerate for 10-30 seconds, or until you spin out the gear, then sit down and spin 10 RPM faster. Hold this cadence for five seconds, then return to normal pace. Repeat 3 or 4 times every hour. Pickups... get out of the saddle and accelerate away from stop signs, over short hills, out of turns or around a car parked in your bike lane--check your mirror!

Nutrition

Keep your glycogen stores high so you can handle more intense riding. Most cyclists have enough glycogen stored in their liver and muscles for about two hours of moderate intensity. When glycogen runs out, the body begins to burn fat, which can lead to bonking. So make sure you ingest 40 grams of carbohydrate per hour during your rides. Most energy bars contain about 40 grams of carbohydrates.

Your glycogen is low after a ride, but your blood flow will remain high for an hour or so. That hour after a ride is a glycogen window during which your body will convert the carbohydrates you eat more rapidly than normal. So eat or drink carbohydrates as soon after a ride as possible to ensure adequate glycogen recovery.

Recovery

Let your body tell you when it's ready to ride again. Your body repairs itself at night, while you sleep. So make sure you get adequate rest. If you need an alarm clock to get up in the morning, you probably didn't get enough sleep.

Goals

Strive to mesh the physical and psychological side of cycling--your training and performance goals--with the social side of life--your family and friends.

Zone Training

Training in specific zones is a results-oriented way to align your heart, your training and your goals. Each zone is a Training Level (TL) associated with a range of heart rates and training effects. The range of heart rates for each zone are percentages of your Heart Rate Reserve (HRR). Your heart rate reserve is the range of heart beats between your Resting Heart Rate (RHR) and your Maximum

Heart Rate (MHR). Your maximum heart rate can be approximated by subtracting your age from 220. You can get closer to your actual MHR by running on a treadmill or cycling up a hill near your anaerobic redline.

Low Aerobic... you burn fat (low octane fuel) and your heart delivers all the oxygen your muscles need. Exercise in this range of heart rates builds cardiovascular endurance. It's the Fat-Burning Zone but you'll lose more weight by burning fat and glycogen and that requires a mix of low and high aerobic exercise.

High Aerobic... you burn fat and glycogen (high-octane fuel), and your heart delivers all the oxygen your muscles need. Exercise in this range of heart rates builds cardiovascular efficiency ~ the ability to transport oxygen to and carbon dioxide from your muscles. Stroke volume, the amount of blood your heart pumps with each beat, is the key to improving fitness. You notice improvement as an ability to exercise longer before dropping back to the low aerobic zone.

Anaerobic Threshold... you are at or beyond the point where your heart can no longer deliver all the oxygen your muscles need. You are burning only glycogen but cannot burn it down to just carbon dioxide. This leaves a lactic acid "sludge" of unburnt sugar that causes your muscles to fatigue. Exercise in this zone builds tolerance to lactic acid accumulation and therefore athletic endurance. You notice improvement as an ability to exercise longer in this zone before your muscles shut down.

Anaerobic Red Line... you are near your maximum heart rate (MHR). Exercise in this zone builds competitive speed by training fast-twitch fibers in your muscles. You notice improvement as ability to exercise faster over a given distance.

Anaerobic Red Line... you are near your maximum heart rate (MHR). Exercise in this zone builds competitive speed by training fast-twitch fibers in your muscles. You notice improvement as ability to exercise faster over a given distance.

Zone Training Calculations

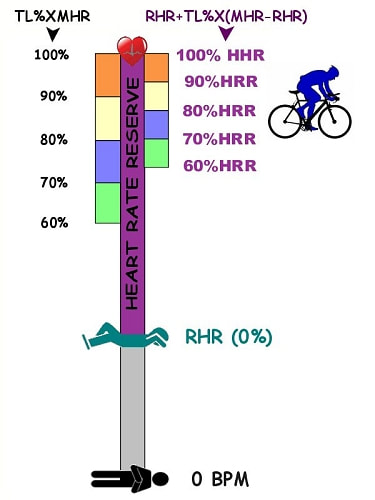

The most accurate way to determine your target heart rate (THR) for a training level (TL) is to base your calculations on a percentage of your heart rate reserve (HRR), not on a percentage of your maximum heart rate (MHR). The diagram below shows you why.

The left side shows zone training calculations based on your maximum heart rate. The right side shows zone training calculations based on your heart rate reserve. If you compare the training levels on the left with the training levels on the right, you'll notice that using your maximum rate instead of your maximum and resting rates results in under training.

The calculations on the right side of the diagram reflect the understanding that your heart operates between your RESTING and MAXIMUM heart rates, not between DEAD and MAX. The calculations on the right side of the diagram reflect:

Do-It-Yourself MHR Test

The calculations on both sides of the diagram use 220-AGE to determine your maximum heart rate. But the 220-AGE is a general formula for the average person. So your zone training calculations will be even more precise if they're based on your actual maximum heart rate.

Find a gradual hill about 2 miles long. Warm up for 15 minutes, then start climbing the hill. Increase your effort gradually until you're within one or two hundred yards of the top, then stand up and sprint as fast as you can. Record the highest number displayed on your heart rate monitor. Rest, then repeat this test a few times to get an average value.

Training Zone Calculators

The calculators below will perform the heart rate calculations for you. If you do not know your actual maximum heart rate, use the first calculator. If you've determined your maximum heart rate with the DIY MHR Test above, use the second calculator.

The calculations on the right side of the diagram reflect the understanding that your heart operates between your RESTING and MAXIMUM heart rates, not between DEAD and MAX. The calculations on the right side of the diagram reflect:

- How your heart actually operates;

- Your fitness, not just anyone your age;

- Changes in your resting rate as fitness improves;

- The goals you seek by not under exercising.

Do-It-Yourself MHR Test

The calculations on both sides of the diagram use 220-AGE to determine your maximum heart rate. But the 220-AGE is a general formula for the average person. So your zone training calculations will be even more precise if they're based on your actual maximum heart rate.

Find a gradual hill about 2 miles long. Warm up for 15 minutes, then start climbing the hill. Increase your effort gradually until you're within one or two hundred yards of the top, then stand up and sprint as fast as you can. Record the highest number displayed on your heart rate monitor. Rest, then repeat this test a few times to get an average value.

Training Zone Calculators

The calculators below will perform the heart rate calculations for you. If you do not know your actual maximum heart rate, use the first calculator. If you've determined your maximum heart rate with the DIY MHR Test above, use the second calculator.

YOU DON'T KNOW YOUR MHR

THR = RHR + TL% × (220-AGE — RHR)